The Lattice of Silence: Ground Plane Antennas and the Art of Nulling

There's a peculiar kinship, I've found, between the meticulous craft of building a ground plane antenna and the restoration of an antique accordion. Both pursuits demand patience, a keen eye for detail, and an appreciation for the ingenuity of those who came before. An accordion, once a vibrant voice weaving stories through bustling squares, can fall silent, its bellows cracked, its reeds tarnished. Similarly, an antenna, designed to capture the faintest whisper of a signal from across the globe, can be crippled by interference, its performance dimmed by a poorly constructed ground plane.

I remember my grandfather, a silent, stoic man, painstakingly repairing a Hohner Monarch accordion he’s had since the 1950s. The air in his workshop was thick with the scent of leather, varnish, and a kind of quiet concentration. He'd painstakingly clean each reed, meticulously align the keys, and gently reinforce the bellows. He’d often say, “It’s not just about fixing it, it’s about listening to it again, understanding what it wants to say." The same principle applies to antenna construction; it’s about more than just wires and metal. It’s about listening to the radio environment, understanding how signals propagate, and shaping the antenna's surroundings to enhance desired signals and minimize the unwanted ones.

The Ground Plane: More Than Just a Base

The ground plane antenna, often overlooked in favor of more complex designs, offers a surprisingly versatile platform for experimentation. While the simplest configuration is a single radiating element mounted above a flat ground plane, the real magic happens when we start to sculpt that ground plane. It’s no longer just a passive sheet of metal; it becomes an active participant in shaping the antenna’s radiation pattern.

Think of the ground plane as a series of reflective surfaces. Each surface reflects the signal, and the interference patterns created by these reflections are crucial to understanding how to optimize performance. A perfect flat plane would create a symmetrical pattern, but the real world is rarely perfect. Buildings, terrain, and even nearby vehicles introduce irregularities that can drastically alter the radiation pattern. This is where the art of nulling comes into play.

Nulling Interference: Sculpting the Radio Horizon

Nulling, in the context of antenna design, refers to the process of creating zones of reduced signal reception. We can strategically position reflective surfaces—elements of the ground plane—to weaken or eliminate unwanted signals originating from specific directions. This isn't about eliminating *all* signals, which is impossible, but rather about minimizing the impact of interference that degrades desired communication.

The underlying principle relies on destructive interference. When two signals of the same frequency are 180 degrees out of phase, they cancel each other out. By carefully adjusting the position and angle of ground plane elements, we can manipulate the phase relationships of reflected signals to create nulls in unwanted directions. The beauty lies in the subtle adjustments—a fraction of an inch or a slight tilt can have a significant impact.

Consider a scenario where you're consistently plagued by a strong signal from a local repeater. Rather than fighting against it, you can strategically position a ground plane element to create a null that points directly at that repeater, effectively silencing it. This technique requires a bit of experimentation and careful observation, but the rewards – clearer communication and reduced noise – are well worth the effort. Simple directional finding tools are immensely helpful for locating interfering signals.

Building for VHF and UHF: A Hands-On Approach

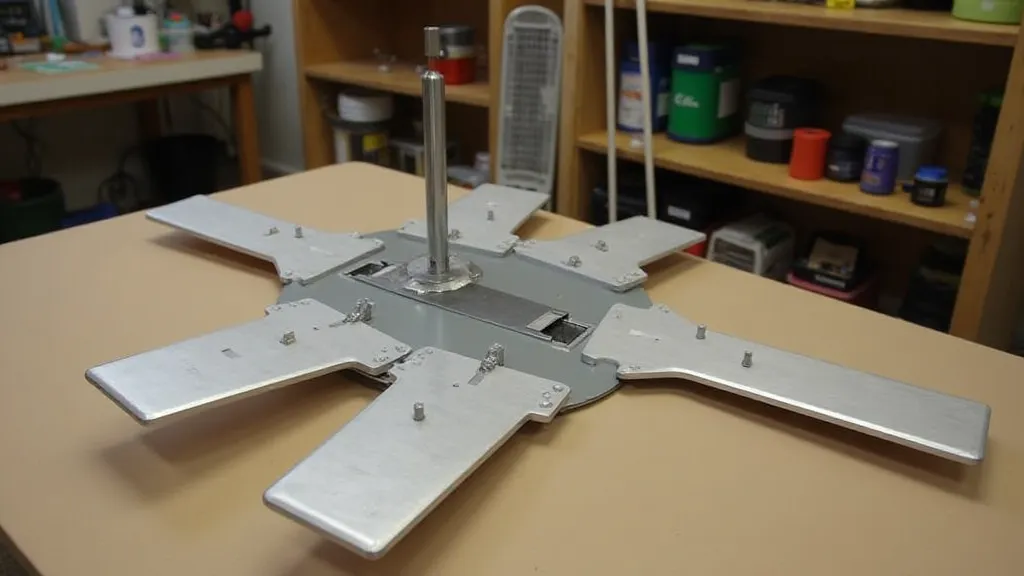

VHF and UHF ground plane antennas are particularly well-suited for this type of experimentation. The shorter wavelengths involved make it easier to manipulate the ground plane elements and observe the effects of those adjustments. Building a basic VHF/UHF ground plane is straightforward: a single radiating element (typically a dipole or a shortened monopole) mounted above a flat ground plane composed of multiple radiating elements (usually vertical quarter-wave monopoles). The key is the accuracy of dimensions, particularly the quarter-wave lengths.

The material you choose also matters. Copper provides excellent conductivity, but aluminum is a lighter and more readily available alternative. Steel is generally avoided due to its tendency to corrode. Regardless of the material, ensure all connections are clean and tight to minimize signal loss. Corrosion can be a silent killer of antenna performance.

Beyond the Basics: Creative Ground Plane Designs

The standard radial pattern of ground plane elements isn’t the only option. Experimentation with different configurations can yield surprising results. Consider a “tapered” ground plane, where the length of the radials varies. This can broaden the front-to-back ratio, improving the antenna's ability to reject signals from behind. Similarly, a “folded” ground plane, where the radials are bent or curved, can alter the radiation pattern in complex ways.

These more advanced designs require a deeper understanding of antenna theory, but the potential rewards – a truly optimized antenna that performs beyond expectations – are considerable. It’s much like restoring an old accordion; the more you learn about its intricacies, the more you can coax out its full potential.

RF Principles: A Foundation for Success

Successful ground plane antenna construction isn't just about following plans; it's about understanding the underlying RF principles at play. Concepts like impedance, standing wave ratio (SWR), and radiation resistance are crucial for troubleshooting and optimizing performance. A high SWR indicates a mismatch between the antenna's impedance and the transceiver's impedance, leading to signal loss and potential damage to the transceiver. Understanding how antenna length, ground plane size, and element positioning affect these parameters is essential.

Simple tools like an SWR meter and a directional antenna can be invaluable for diagnosing problems and fine-tuning the antenna’s performance. The process is iterative; adjust, observe, and repeat until you achieve the desired results. It's a journey of discovery, much like the meticulous process of re-voicing an old accordion – finding the right combination of reed profiles and placement to achieve the desired tone.

A Legacy of Ingenuity

Building a ground plane antenna, and more specifically, sculpting its ground plane to null interference, isn't just a technical exercise; it's a connection to a long line of radio enthusiasts who have embraced ingenuity and craftsmanship. It’s a way to appreciate the elegance of simple designs and the power of observation. Just as a meticulously restored accordion breathes new life into a forgotten melody, a well-designed ground plane antenna amplifies the voice of the radio operator, allowing them to connect with the world, one carefully sculpted reflection at a time.